I’ve always been fascinated by the stories of how developers got their start in the industry, and Dylan Cuthbert’s journey is the stuff of legend. At just 18 years old, while working at Argonaut Software, he managed to crack the copyright protection on the Nintendo Game Boy and create an impressive 3D tech demo for the handheld. Just a few weeks later, he was on a plane to Nintendo’s headquarters in Kyoto, a meeting that would lead to him working alongside Shigeru Miyamoto to create the iconic Super Nintendo game, Star Fox.

Table of Contents

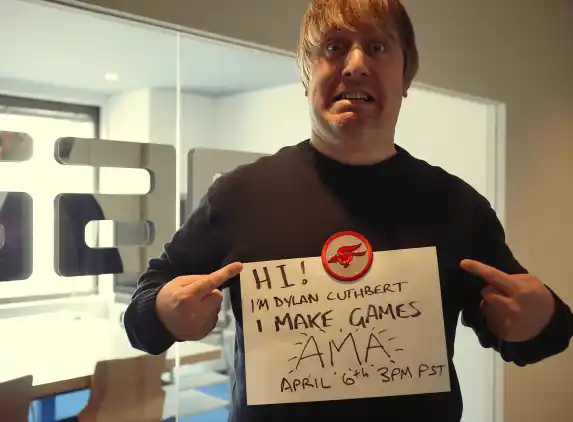

Over his thirty-year career, Dylan has worn many hats: programmer, director, and CEO of his own independent studio, Q-Games. He’s been at the forefront of technological innovation, from bringing 3D graphics to the Game Boy to pioneering indie development on the PlayStation 3 with the PixelJunk series.

In this look back at his incredible career, I want to explore how a young programmer from the UK ended up at the heart of Nintendo’s golden age, the lessons he learned from industry legends, and how he continues to innovate with his own studio in Kyoto.

The Hack That Started It All

It’s amazing to think that Dylan’s career started because he was good at reverse-engineering hardware. He told me he created a Z80 emulator on the Amiga to simulate what he imagined the Game Boy’s architecture to be. He wasn’t far off, which gave his team a huge advantage when they got their hands on the real hardware. The result was a 3D tech demo called Eclipse, which they showed to Nintendo at CES in Las Vegas.

Nintendo was so impressed that they flew him and his boss to Kyoto. They signed a contract to turn the demo into a full game, which would become X (1992), one of the only games to feature 3D wireframe graphics on the Game Boy. It was a remarkable technical achievement that showcased what was possible on the limited hardware. It was this work that led directly to the development of Star Fox.

To get polygonal 3D graphics working on the Super Nintendo, the team at Argonaut developed the legendary Super FX chip, a co-processor that was built directly into the Star Fox cartridge. This was a groundbreaking innovation that allowed for a level of 3D performance that was previously thought impossible on a 16-bit console. This kind of hardware-pushing wizardry reminds me of the story behind another technical marvel, Crysis.

Learning from Legends

Working at Nintendo in the early ’90s meant collaborating with some of the most influential figures in the history of video games. Dylan shared with me some of the key lessons he learned from these masters. From Yoshio Sakamoto, he learned not to make games too difficult, as not everyone is a hardcore gamer. From the legendary Shigeru Miyamoto, he learned the importance of re-evaluating a feature and being willing to cut it if it doesn’t work, no matter how attached you are to the idea.

He shared a wonderful memory from the final days of Star Fox development. He and Miyamoto were waiting for the last bug reports to come in, and at three in the morning, Miyamoto had a craving for his favorite snack from his university days: McVitie’s chocolate biscuits. They went out on a late-night snack run, a surreal and humanizing moment with a living legend.

This experience deeply influenced his own approach to game design. He even had a hand in one of gaming’s most famous easter eggs. The composer Kazumi Totaka hid a little tune, now known as ‘Totaka’s Song,’ in many Nintendo games, and its first-ever appearance was in Dylan’s Game Boy title, X. He told me he was the one who programmed the secret area where the song was hidden. This kind of creative, playful spirit is something I also saw in my exploration of the development of Sonic Generations.

Founding Q-Games and the PixelJunk Series

In 2001, after years at Nintendo and then Sony, Dylan decided to realize his lifelong dream of starting his own studio. He founded Q-Games in Kyoto, Japan. The studio’s big break came with the launch of the PlayStation Network, which opened the door for smaller, downloadable games. This led to the creation of the PixelJunk series for the PS3.

Each PixelJunk game was a unique experiment, exploring different genres and art styles. From the exceptional tower defense of Monsters to the artistic platforming of Eden, the series showcased the studio’s incredible creativity and versatility. Dylan told me his goal was to return to 2D game design, but with the full power of the PS3’s 1080p output, creating games that were both nostalgic and modern.

Today, Dylan and Q-Games are still creating unique and innovative titles, like The Tomorrow Children. His journey from a teenage hacker to the head of a respected independent studio is an inspiration. It’s a testament to a career built on passion, curiosity, and a relentless desire to push the boundaries of what’s possible in video games. It’s a story that highlights the magic of the indie spirit, a spirit also found in the history of studios like Psygnosis.

retrogamer magazine, September 2025, p. 58-63

- Snatcher: A Look Back at Hideo Kojima’s Cyberpunk Cult Classic

- A Tribute to Psygnosis: The Studio That Defined a Generation of Cool

- Dino Crisis: Unearthing the Secrets of Resident Evil’s Dinosaur-Filled Cousin

- Grim Fandango: The Unforgettable Noir Adventure of LucasArts’ Golden Age

- Sonic Generations: How a Tale of Two Hedgehogs United a Divided Fanbase

- The 108 Stars of Destiny: A Deep Dive into the World of Suikoden

- The Arcade Revolution: A Guide to Capcom’s Legendary CPS-1 Games