Explore the life and legacy of Philippe Soupault, pioneering Surrealist poet and writer—his poetic awakening, groundbreaking automatic writing, clashes with Breton, and role in resistance during WWII.

Table of Contents

- 1. 1. Beginnings: Illness and Inspiration

- 2. 2. Discovering Surrealism

- 3. 3. Unlocking the Unconscious

- 4. 4. Love, Dada, and the Joy of Chaos

- 5. 5. Breaking with Breton

- 6. 6. Novelist and Outsider

- 7. 7. Journalism, Resistance, and Renewal

- 8. 8. Final Years and Lasting Influence

- 9. 📌 Quick Recap: Philippe Soupault’s Journey

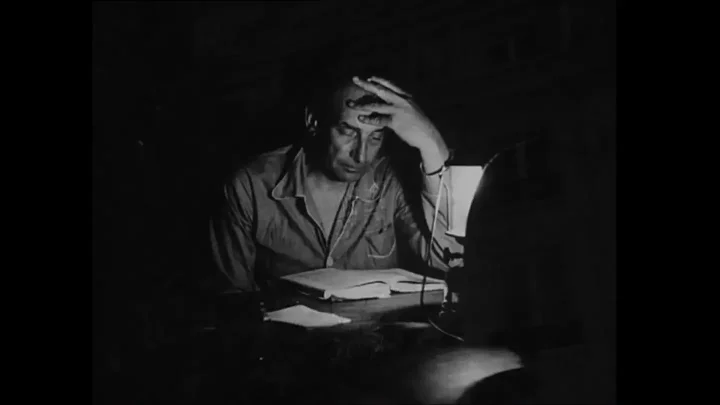

“I had the idea to write this film shot in the head.”

— Philippe Soupault

1. Beginnings: Illness and Inspiration

Philippe Soupault’s poetic journey began in the shadow of illness. In 1916, after nearly dying from an experimental typhoid vaccine, he experienced a surreal inner disturbance—a “rumbling in the head”—that sparked his desire to write. This moment planted the seed for a lifetime of creative exploration.

2. Discovering Surrealism

Soupault sent his early poems to Guillaume Apollinaire, who encouraged him and introduced him to André Breton. The trauma of World War I bonded them through a shared revolt against violence, conformity, and bourgeois culture.

Note:

This rebellion would become the foundation of Surrealism, a movement grounded in dreams, the unconscious, and poetic freedom.

3. Unlocking the Unconscious

Influenced by Freud, Rimbaud, and Lautréamont, Soupault embraced automatic writing—letting the unconscious speak without censorship. Alongside Breton, he co-wrote Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields, 1919), considered the first full experiment in this technique.

Example:

They wrote separately during the day, then read each other’s texts at night—blending spontaneity with collaboration.

4. Love, Dada, and the Joy of Chaos

In 1919, Soupault fell in love with a dancer named Mick, for whom he wrote numerous poems. That same year, he became active in Dada, influenced by Tristan Tzara’s anarchic energy. He took part in provocative Dada events, thriving in their chaotic and rebellious spirit.

5. Breaking with Breton

Tensions with Breton emerged. Soupault rejected the group’s drift into occultism and resisted Breton’s rigid control. When he published a novel—a form Breton had banned—he was publicly humiliated. Eventually, he was expelled from the Surrealist group in 1926 for “disordered literary activity.”

Quote:

Breton’s reaction? He published blank pages in Littérature to mock Soupault’s writing.

6. Novelist and Outsider

Undeterred, Soupault continued writing. His 1928 novel, The Last Nights of Paris, blended noir realism with Surrealist tones. In 1929, he published The Great Man, a biting satire of the industrial elite. The novel angered Louis Renault, who tried to suppress it.

Note:

The personal and political often intertwined in Soupault’s work—fueling both his art and his conflicts.

7. Journalism, Resistance, and Renewal

In the 1930s, Soupault turned to journalism for stability, reporting across the U.S. and Europe. During World War II, his anti-fascist stance led to imprisonment and torture in Tunisia. After his release, he joined the French Resistance, rediscovering both his voice and resolve.

8. Final Years and Lasting Influence

Soupault’s later life was filled with both grief and productivity. He lost his wife Muriel Reid to suicide but remained active—broadcasting radio programs, mentoring poets, and publishing his collected works. He died in 1990, remembered as a founding Surrealist who never abandoned his independence.

📌 Quick Recap: Philippe Soupault’s Journey

- Survived near-death experience that sparked his poetic awakening

- Co-created automatic writing with Breton (Les Champs Magnétiques)

- Rejected dogma, clashed with Surrealist leadership

- Wrote groundbreaking novels blending satire and Surrealism

- Joined resistance during WWII; later became a public intellectual

- Left a legacy of poetic freedom, wit, and unwavering independence