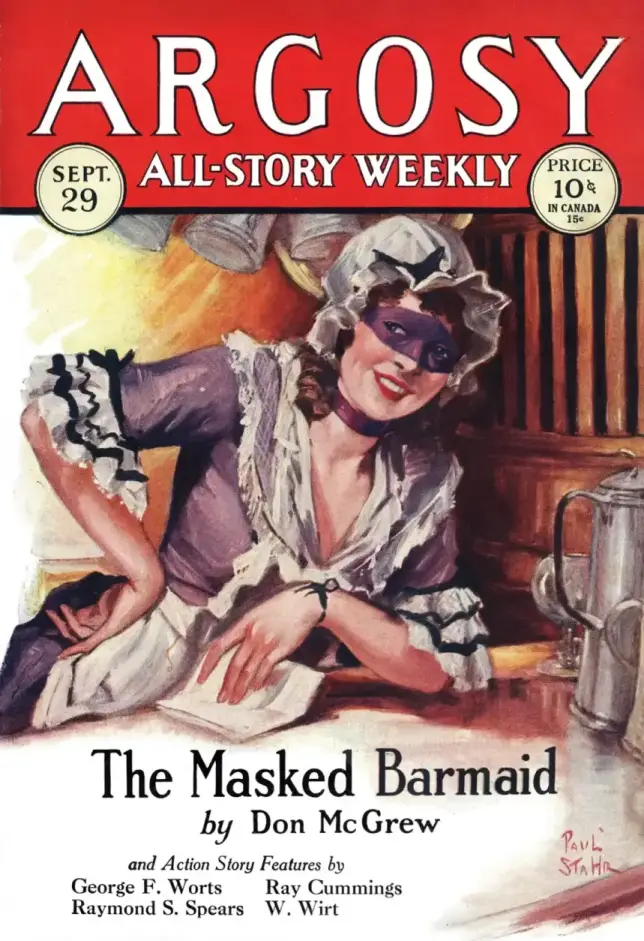

Set sail with Don McGrew’s “The Masked Barmaid” into a deadly mystery aboard the Mary Louise. The Goulds arrive from the sea, bringing a web of treachery, intrigue, and suspicion that will cast a dark shadow over everyone on board.

Table of Contents

Book Information

- Title: The Masked Barmaid

- Author: Don McGrew

- Publication: Argosy All-Story Weekly

- Volume: 198

- Number: 2

- Publication Date: Saturday, September 29, 1928

CHAPTER I. ADRIFT.

The events involving the masked barmaid occurred after I had reached the age of thirty, I must needs hark back to the year 1771, and the mysterious tragedy on the schooner Mary Louise, which took place when I was a lad of twelve, bound on a trip from England across the Atlantic to join my widowed father in Boston.

The Mary Louise was owned by my father, then a builder and shipper in Boston. She was sailing under the command of Captain Andrew Randall, a dour, spare Yankee, about forty years of age, with gaunt, dyspeptic features; and we were about halfway between Bristol and Charleston, our first port, when, having weathered a heavy storm, we sighted a tossing speck upon the distant waters.

The skipper, with Roaring Bill Gentry, the mate, was standing near me on the poop at the time. Randall studied the speck for a moment through his glass, his thin lips drooping bitterly at the corners. He had a long, clean-shaved upper lip, and a bony, uplifted chin, with a sharp-pointed beard beneath it which made me think of the tuft worn by a cantankerous billy goat.

“Hell!” he said at last, lowering the glass. “Looks like a lifeboat.” His cold, furtive eyes shot a glance at Gentry from under his lowering brows, and he went on, gruffly; “I suppose, Mr. Gentry, we’ll have to stand in closer to see if anyone’s aboard her.” Upon which he favored me with a queer, sidelong glance, and went below.

Beyond a brief, “Aye, aye, sir,” Gentry made no comment—save that he gave me a glance on his own account, and the shadow of a wink. He was a huge and terrific man, who strode about the decks in a great blue coat, with shining brass buttons, and his breath hanging behind him on the cold morning air, like tobacco smoke.

His bronzed, clean-shaved features were as craggy as granite. Even then, though he was but thirty, the lines from nostrils to mouth-corners were deeply indented, while the skin on his cheeks resembled heavy folds of pig’s-hide; and his eyebrows, jutting out to either side of his fierce, horny nose, were so long, and so thick, that he had twisted them into spikes, and bent them upwards, like a devil’s horns.

Yet, when he smiled at me, with the merriest of twinkles in his keen blue eyes, I smiled in return; for while Captain Randall had the aspect of a man with many secrets and no confidants, and seldom spoke, save to snarl out an order through his long nose, Gentry had proved, from the very first, to be the best of company. He was an accomplished mimic, could imitate a dozen and one birds and animals, and was also a raconteur to bring the eyes of any lad popping from his head.

Sometimes he would poke me in the ribs with his thumb, call me “Old Sober Sides,” and ask me if the cat had taken my tongue; sometimes he would “wall” his eyes at me, and twitch his spiked eyebrows in a way to make me shiver; but always, when I quailed, he would laugh uproariously, and reassure me with a slap on the back. Hence I was quite sure by this time of Roaring Bill Gentry, and felt that he and I shared identical opinions of the crusty, furtive skipper.

“That’s right, Davy!” the mate cried, noting my smile. “Let a reef out of that jaw tackle—it’s allus best.” Then, as we drew nearer the little boat, and he raised his glass again, he swore mightily. “Why, by the Flying Dutchman!” he cried. “There is people aboard—and—” He broke off, and stared again. “Yes, by thunder!” he went on. “A woman and a babby, too!”

“A baby?” I cried.

“Look for yourself,” he said, handing me the glass.

And, in a moment, I was athrill with excitement, and begging Gentry to crowd on more canvas; for there with three men sat a woman hugging a bundle close to her breast.

We soon had them aboard. The baby, whose name was Virginia, was not quite a year old, and had apparently suffered comparatively little from her travail; but the mother, Mrs. Jonathan Gould, a tall, slender woman, with calm gray eyes, and a wealth of dark tresses, was very weak.

With them were two sailors, and a man named Anthony Gould—a tallowy fop, with pale eyes, and a drooping, sensual mouth. And they proved to be survivors from the Glory of the Ocean, a brig in which the Goulds had been returning to England from the Bermudas. Jonathan Gould, the baby’s father, had gone down with the ship. He and Anthony were cousins.

From the very first I disliked Anthony Gould, for he had no word of thanks for his deliverers, was forever finding fault with this or that, and was about as pleasant, on the whole, as some flabby dank fish. And Gentry once confided to me that the man gave him the “squeejie-meejies.” Moreover, it soon became apparent that Mrs. Gould shared our opinion of Anthony. From the time she came aboard she never uttered one word of complaint; she was always kind when addressing me or Roaring Bill; but, weak as she was from exposure, her eyes flashed fire at sight of Anthony.

Mrs. Gould grew steadily weaker instead of stronger; and often I caught her looking at me strangely. I also saw her studying the faces of Captain Randall and Gentry at different times. And finally, when we were alone one day, she beckoned to me.

“David,” she said, “I want the first mate.”

I returned shortly with Gentry; and, when the door of her little stateroom was closed, she said, without preamble, “Mr. Gentry, I’m not going to live.”

“Never say that, m’lady!” Gentry cried.

“I know!” she replied. “And this baby will be the only heir to her father’s estate—if she lives.”

“Lives, m’lady? Beggin’ your pardon, but she’s a healthy little tyke.”

“Praise God for that! You see, if she dies, that creature Anthony would be next in line for the estate.”

“A-h-h!” said Gentry, with a slow nod.

“And I don’t trust him! Now you’ve an honest face, my man”—here Gentry reddened—“and I’m going to ask you to accept a mission.”

“If so be it I can, I’m your man, m’lady,” Gentry answered promptly.

She thanked him, with evident emotion, and thrust a heavy wallet, and an oilskin packet into his hands. “Put them away—quickly!” she whispered, with an apprehensive glance at the door. And, when Gentry hastily complied, she went on, in low tones, “There are ample funds in the one, and letters and a birth certificate in the other.”

Here she lifted the coverlet, disclosing the baby’s right cheek; and on the temple, merged with the hair line, close to the ear, we saw a purple birthmark, not larger than the ball of one’s thumb, and shaped somewhat like a violet.

“Once I grieved horribly over that,” she continued. “Now I am grateful for it. She was born in the Bermudas, you see, and none of her relatives—except that wastrel, Anthony—has seen her. With that mark, identification shouldn’t be difficult.”

Mrs. Gould then explained that she wanted the baby delivered to her sister, Gertrude Channing, who lived near London, on Bromderry Heath; and she assured Gentry that he would be well reimbursed if he could arrange the trip.

“Why, m’lady,” said Gentry, heartily “I’ll do it, if so be it I can.”

She sighed with relief; but immediately her chiseled features became grave again. “There’s another thing,” she resumed. “I’ve made a will. My husband’s will, which was placed on file in London, leaves everything to me. The will I have written leaves everything to my baby, and the estate—with some shipping interests—is valued at over a half million pounds. I have named my sister Gertrude as executrix, to be baby Virginia’s guardian until she reaches the age of twenty-one.

“But in case Virginia dies—there is still another journey across the Atlantic, too—I have provided that Gertrude, or her heirs, will come into the estate. Otherwise Anthony—in case the baby died—would come into the property as my husband’s next of kin. And I want to sign this will now, with two witnesses.”

“Cap’n Randall and myself, perhaps?” Gentry suggested.

“No!” cried Mrs. Gould. “I don’t trust him, either. Can’t you think of some honest hand aboard?”

Gentry thought a minute. “I’ll get the coxsw’n, Tom Norton,” he said at last.

“Can he keep his mouth shut?” she asked. “You understand, of course, that Anthony must not dream of this will until it is safe in Gertrude’s hands.”

“Tom Norton’s silent as the grave, m’lady,” said Gentry.

“Very well, then. I know David will be, too. He’s a knowing lad, is David.”

And then, Gentry returning shortly with Tom Norton, the swarthy coxswain, the situation was briefly sketched to him. The will and order were produced and duly signed by Mrs. Gould, with the scrawling signatures of Gentry and Norton attached, as witnesses. I remember well how Norton chewed his tongue as he seized the quill, and how he finished the last letter with a little ‘curlicue,’ shaped somewhat like a bird’s tail.

“There!” Mrs. Gould exclaimed, sinking back on her pillow and handing the papers to Gentry. “I trust that will frustrate anything Anthony Gould may have in mind.” And she placed some sovereigns in Norton’s hand.

“Understand me,” she continued, addressing Gentry, “I don’t fear actual murder—at least aboard this ship. He wouldn’t dare. What I fear is that he will take charge of the baby when you get to Charleston and go ashore with her, and then—no one will ever see her again. I’m giving you an order, Mr. Gentry, placing the baby in your charge till she’s delivered to Mr. Waltham or my sister.”

“And you’re not going to tell Anthony about this, m’lady?” he inquired.

“No,” she said.

“But, m’lady,” Norton put in, “if he knows ’bout this here docyment, right off, he’d never do anything, would he? What good would it do him to harm the baby or lose her, in which case he’d not get the property nohow?”

“You’re not safe in harbor yet. Best insure the safety of the baby and the will by waiting till you get to Charleston.”

This being agreed on we left her; but all of us started a little when we emerged into the main cabin, for Anthony Gould had entered, and was now seated beside the table under the stern ports.

CHAPTER II. CONSPIRATORS.

The big first mate wore an abstracted air as we came on deck. He pursed his lips and looked at Norton in sidelong fashion.

“I don’t think he could’ve heard anything,” he said presently.

“Right you are, sir,” said Norton. “Cap’n may be wonderin’, though.”

“Let him,” Gentry grunted. “And now, remember—mum’s the word.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” said the coxswain, and went forward.

“See you don’t forget that, too, Davy,” Gentry said to me.

“I won’t, sir,” I replied fervently.

“Why,” said he, “I tell you, sonny, I wouldn’t put it a fathom past that swab to cut that babby’s throat, I wouldn’t.”

“Oh, I believe that!”

“Why, by the Flying Dutchman!” he exclaimed, “take a look at them deadlights o’ his. That there estate’s valued at over half a million pounds, sonny. You keep mum, that’s your cue, and I’ll keep my weather eye on that swab, in case m’lady slips her cable.”

I assured him heartily that I would do his bidding.

True to her predictions, Mrs. Gould died two days later, and she being consigned to the deep, the role of nursemaid fell to my lot. Gould showed no disposition to concern himself with the infant’s care, and the greasy cabin boy had other duties and was quite out of the question.

There were other occupations on board that would have appealed to me more, but whenever I thought of the danger that hovered over her, I began to regard myself as one of her guardians.

“Ha!” cried Gentry, catching me playing with her toes one day. “Well, now, you needn’t fly the red ensign, my lad. Nothin’ sweeter than a gal babby, by the Flying Dutchman!” And he looked down with a smile as the baby closed one hand around his big, horny finger. “But you see here, Davy,” he continued, “mum’s the word—now you remember. Keep a silent tongue.”

I nodded energetically, for a new circumstance had arisen to increase my apprehensions. Whereas the captain had kept to himself for the most part, before the rescue, he and Gould had come by now to be as thick as thieves. They were often engaged in guarded talk. If I approached they fell silent; if I lingered near by they frowned me off or moved away; and one night, when I came on deck unexpectedly, I heard Captain Randall say:

“No! and an end to it. It’s twenty thousand pounds or nothing!”

Just then I turned to go down before they should sight me; but the captain heard me and called to me quite sharply.

“Look here!” he demanded, seizing my wrist in a fierce grip, “why are you prowling around at this hour o’ the night?”

“Sir,” I said, “I had to feed the baby.”

“Ah!” he said, in a softer tone. Then his grip tightened again, and he bent over to peer menacingly into my face. “If—” he began—but here Gould coughed, and Randall released me, saying, “Best go below now, sonny; sleep makes a boy grow.”

Thoroughly aroused, and filled with fresh terror, I reported this happening to Gentry at my first opportunity. His eye watched me narrowly; and when I mentioned the sum the captain had named, he gave vent to a low whistle.

“Twenty—thousand—pounds!” he said, slowly. “Something big’s afoot, I’ll be bound.” He thought a moment. “Well, I can’t fathom it yet, but we’ll bide the time, and maybe we’ll strike bottom yet.”

We received some glimmering of light before many days had passed. When we were one day out of Charleston, our first port, the baby was suddenly taken ill, with cramps. Thereupon Captain Randall ordered the after-cabin cleared.

“I’ll have to quarantine her,” he announced. “This may be cholera.”

As soon as possible I sought the mate. “Mr. Gentry,” I cried, “do you think they’ve poisoned her?”

He rubbed hard at his cheek. “Why, as to that I can’t say,” he replied, looking away over the water, with a frown. “If I was sure, I’d step up in a brace of shakes I would. But you see how it is, Davy: I’m on’y mate; he’s cap’n; and I can’t charge him with crime when I ain’t got no manner o’ proof, now can I? No, says you, I can’t. Well, then, what I say is this: We’ll just have to stand by, like, to see which way the wind blows.”

We were soon to know. That night Captain Randall came out of the after-cabin, and announced that the baby had died.

“Ah, and a pity it is!” said Gentry, shaking his great head sadly. “Well, cap’n, I suppose we’ll bury her right off?”

A heavy fog had fallen shortly after sundown, and I could not see Captain Randall’s features clearly.

“No,” he said. “Mr. Gould wants to bury her ashore.” He turned to mount the poop. “Oughta make it into Charleston by to-morrow, less’n this fog holds,” he said.

CHAPTER III. A MURDEROUS ATTEMPT.

Wildly elated, my first impulse bade me pick her up, and rush with her to Gentry, using the cabin door as an exit. I was certain that neither Gould nor Randall would dare to harm the baby or me once we reached the open deck and Gentry’s protecting arms; but when I ran to the cabin door I found it locked. Then, as I turned back, I heard footsteps in the companionway.

Scurrying for the cellar ladder, I barely had time to drop the hatch over my head before a key grated in the lock of the cabin door, and some one entered.

Being sure that it was either Gould or Randall, I went down that ladder step by step, holding my breath for fear of making the slightest sound; but the man above me must have heard the hatch drop, or some other sound of my movement, when he was unlocking the door; for he ran first into the baby’s little stateroom—as I judged by the sound—and then dashed for the hatch.

Abandoning caution, I released my hold on the ladder and dropped to the cellar deck. As the hatch was thrown aside, and the fitful rays of the murky cabin lamp lessened the darkness of the hold, I scrambled over a hogshead and into the narrow gaps between the cargo and the upper deck, through which I had worked my way aft but a short while since.

Nor was I any too swift in my movements; for the man above me, though he could not see me, heard me scrambling; and, as he cursed viciously, I recognized the voice as that of Captain Randall. In the next second he had dropped into the hold, and began beating about here and there with a belaying pin.

“Come out o’ that, you swab!” he yelled. And I knew, by the sounds, that he was striking into the black spaces behind various hogsheads and crates. “Oh, shiver my sides!” he cried, “why didn’t I bring a light?”

Safely wedged, by this time, between a hogshead and the upper deck, and beyond his reach, I lay quite still; and after a moment of muttering, Captain Randall moved over to the ladder.

“I’m going aloft to fetch a glim,” he gritted. “Better come out now, and take what I give you. If you don’t, by thunder! I’ll give you three hundred lashes, and keelhaul you besides, or my name ain’t Andrew Randall.”

He paused for a moment, waiting for an answer; then, snorting viciously, he ran up the ladder and into the cabin.

Long before he came back I had crawled far forward; and when at last I reached the upper deck I hurried to the spot in the waist where I had left Gentry and Norton. There I found Gentry, but no sign of Norton.

“What did you find, Davy?” Gentry whispered fiercely. “What did you find?”

“The baby’s alive!” I gasped, when I could get my breath. And I recounted my adventures to him.

“Well, by the Flying Dutchman!” he exclaimed, when I had finished—and it seemed to me that his eyes flared like lamps in the fog! “So that’s it!”

“What’s it?” I asked.

“Why,” he said, in easier tones, “looks to me like cap’n drugged her, maybe. He’s got a medicine chest, you know. Also looks like they didn’t have the nerve to finish her, out and out. Figgers to cast her adrift somewheres ashore, I shouldn’t wonder.”

“But you can stop that!” I cried. “You can walk right in and demand that baby. Mrs. Gould gave you the right.”

“No,” he said, “I can’t. A mate’s a mate, and a cap’n’s a cap’n, while at sea, my son.” Then his tone changed. “But you see here, now: I’ll take care o’ her, soon as we drops anchor. They don’t intend to murder her, now you can lay to it. Otherwise they would have finished her, out and out. Yes, sir; she’d be food for fishes by now, and you can lay to it.”

“But I’m afraid!” I cried. “Where is the coxsw’n? He’d think as I do, I’ll wager.”

“Oh!” he said slowly. “Well, now, maybe two heads is better’n one, at that. He went for’a’d.” He lifted his head and listened as some one stumbled along the deck, working his way aft. Although he passed within a few feet of us, the fog was so thick by now that we could not see him. “You stay here a bit till I gets Tom,” Gentry then went on.

“I’d rather go with you,” I said nervously. “Suppose Captain Randall suspects that was me in the cabin, and he comes prowling about, looking for me?”

Gentry laid a reassuring hand on my shoulder. “Like as not when he gets done lookin’ over that cellar he’ll figger it was rats he heard. We’ve got ’em aboard big as a rat terrier dog, about. ’Tain’t likely he’ll fathom that dodge—you goin’ through the hold, I mean. No, sirree—and he’ll think quite awhile, anyway, I take it, afore he lays his hooks on a son of ship’s owner. But in case he does come lookin’ about, Davy, you just lay doggo here, and duck behind the gig. I’m off to get Tom.”

With that, Gentry left me; and for a space I stood there, crouching beside the bulwarks, and starting apprehensively at every footfall on the deck. And I was still crouching there, listening for Gentry’s return, when the seaman beating the warning bell yelled in sudden fright, and dropped the bell to the deck.

Simultaneously the lookout bellowed hoarsely; a tall, ghostly ship loomed up out of the fog on our port bow; and the Mary Louise, with her booms swung to starboard, struck an outbound square-rigger, the Hespion, a glancing blow amidships, and slithered along her port side with a fearful crashing of spars.

Fortunately, there was little breeze, and neither ship was making more than headway through the long ground swells, or the sharp bows of the Mary Louise might have crushed the Hespion’s side. As it was, the Hespion’s lower spars overlapped the schooner’s port side; and pandemonium reigned. Spars snapped; shrouds were ripped away; blocks came tumbling down, along with tangled ropes and billowing canvas; and above all the shouting and cursing there rose the terrified wail of a lookout as he pitched out and downward into the sea.

At the first sound of the collision I was gripped in a panic of terror and indecision. If I remained where I was, one of the falling spars might crush the gig, and me with it; if I went overboard to escape the missiles I might not be picked up; and if I ran along the deck to one of the companionways I might be crushed while en route. And in my extremity I yelled aloud, calling for Roaring Bill Gentry.

My yell was still quavering in the air, so to speak, when something came whipping out of the fog and struck the bulwarks close to my head. At the instant I thought it was a small block from the rigging; but even as I dodged I realized that it was a belaying pin, thrown with murderous intent.

Instantly I turned to dive between the gig and the bulwarks, being now certain that my yell had disclosed my whereabouts to Gould or Randall—either one of whom, I was sure, would welcome this as an opportunity to throw me overboard under cover of the confusion. But I was not quick enough for my enemy.

Iron fingers caught the back of my jacket; I could not repress a scream of fright; and then my scream was cut off sharply as my throat was gripped savagely from behind. In the same second I was caught at the trouser leg and flung over the starboard side and into the sea.

Luckily for me I had long since learned to swim. So in an instant I had stripped myself of my jacket, and had kicked off my low shoes; and, thus lightened, I began swimming about in the wake of the Mary Louise, searching for any bit of floating debris that might help me keep afloat. Nor was I long in finding what I sought; for my hand fell on a broken spar end, which I seized eagerly. Then I began calling out for help.

There were at least two others in the water making the same appeal at the time; moreover, the men aboard the Hespion and the Mary Louise were shouting at one another, or chopping away with axes at the tangled rigging, and either did not hear or had no time at the moment in which to put over a boat.

For that matter, Captain Randall never did put a gig over the side. The Mary Louise sheered off almost immediately after the collision, and went limping off into the fog; and it was not until ten or fifteen minutes later that a gig from the Hespion picked me up. One of the Hespion’s crew was also rescued from the waters a moment later.

Once I was safe in that gig, I began to hope that the Hespion would have to put back to port for repairs. But in this I was disappointed. She had cleared for Rio, out of Charleston, and was well supplied with extra spars and an extra suit of sails. When daylight came, and the fog cleared, the Mary Louise was not in sight; we reasoned that she was now well on her way to Charleston; and, as for the Hespion, her repairs were well under way, and she was wheeling away to southward before noon observation.

Captain Mathews, the Hespion’s skipper, was a fair man; I never met a fairer; but he was also a strict taskmaster. After listening to my story, he said: “Looks to me like that skipper heaved you over, sure enough. He must’ve figgered it was you worked your way back to that there cabin, sonny, and saw that kiddie alive after he says she’s dead. Plain as print to me he means to help that Gould get the estate. But to-day’s to-day, sonny; bein’ as I’m shorthanded, you goes to work in the galley.”

Hence, when I finally reached Boston, after eight months or more of adventuring, I was sick to death of sousing bilges, greasy pannikins, and foul-smelling quarters; and I vowed I would never put to sea again.

CHAPTER IV. FACE TO FACE.

When I reached home at last, and was nearly crushed against my father’s broad chest, I learned that the baby had been reported dead and buried at sea, just before the Mary Louise reached the port of Charleston, and that Gentry had never mentioned the will to my father!

“That isn’t all, either,” my father declared. “Tom Norton was logged as ‘missing overboard’ same night you were.”

“Then Gould must have heard something about that will when he came into the cabin that day!” I cried.

“I don’t know, I don’t know!” my father muttered, striding about his study like one possessed. He was a very large and violent man, with thick, black eyebrows that moved with every emotion; an exclamatory, impetuous man, with a quick, high temper, but the most generous of hearts.

“No, sir,” he went on, “I can’t say as to that. I put the Mary Louise back to Bristol—Gentry, Randall and Gould all with her. When they dropped anchor here, I read the log, and everything was there. So I never thought for one instant but that you’d been knocked overboard in that collision. But see here: will you tell me why Gentry never said one word to me about his suspicions, or sending you into that cabin?”

I shook my head. It was beyond me.

“Well, I’ll tell you!” my father cried. “I think he decided to profit by that will himself. At any rate I’ll be certain of it if he doesn’t turn the documents over to Mrs. Gould’s sister. Don’t you see the possibilities, my boy? Randall said the baby was dead; you told Gentry she was alive. That made Gentry certain that they shied at murder, but intended to drop her somewhere ashore. But even before that—why, what was to prevent him from knocking Norton overboard while you were in that cabin?”

“I couldn’t believe it of him!” I cried.

“Well, you can see the opportunity he had, can’t you? No one knew of the will but you three—you, Gentry, and Norton. If Gentry could get rid of you two, he had the chance to sell that will to Gould, or blackmail him with it. Yes, sir, I’m going to believe they’re all in it now, till I get proof to the contrary.”

Much as I hated to believe it, father’s conclusions seemed close to the mark; for, by the time the Mary Louise had returned to Boston, after a return voyage from Bristol by way of Rio and Havana, father had written to Gertrude Channing, Mrs. Gould’s sister, and received a reply saying that Anthony Gould had established his claim to the estate. Captain Randall’s log had been accepted as proof of the demise of Mrs. Gould and the baby Virginia.

Gentry, she said, had not visited her, nor made any report whatsoever concerning the will. And her barrister had informed her that she could, of course, do nothing without that all-important document.

“There!” said my father. “I knew it. Maybe I can’t prove anything—but wait until I set eyes on that pair. Just wait!”

I was with father in his office some three months later when the Mary Louise put in, and Captain Randall and Gentry were ordered to report. Randall was admitted first, while Gentry waited in the anteroom. The skipper stopped dead at sight of me, and swallowed with a horrible, choking sound; and my father, who was breathing so hard his breath fairly whistled through his nostrils, launched into a tirade before the man could regain his composure.

But as a lawyer my father would have been a failure; for he fired my whole story at Randall, interlarded with oaths. Then he demanded:

“Well, what have you got to say to that?”

“I never dreamed that boy had been back in the cabin!” were Randall’s first words. He licked at his lips, shuffled his feet, and twisted his hat about in his hands. “I never dreamed but what your boy had been knocked over by a falling spar, or something, sir, I tell you.”

“Who did you think had been in the cabin that night?”

“Didn’t know as anybody had. Did think I heard some one in the cellar—thought likely it was the cabin boy, stealin’ raisins, maybe. Only a kid could’ve worked his way back over that cargo.”

“What about that will? Do you mean to tell me you knew nothing of it?”

“Yes, sir, I do. How could I know anything about it? Gentry never yaps to me. Neither does Norton or this boy here.”

My father snorted. “Will you deny that the baby was alive when David went into the cabin?” he cried.

“Certainly!” Randall declared, with more assurance. His eyes were sickly, and furtive, but they gleamed now with defiance. “I’m not crazy!” he snarled. “That baby was dead as bilge. I ought to know. I—”

“Yes, I guess you should!” my father cut in. “You got panicky that night, after you heard some one in the cabin, and finished the job right. That’s my belief.”

“Them’s hard words,” Randall declared with growing truculence. “You can take your damned billet for all me—I’m done with you. But there ain’t a thing wrong that you can prove on me, I know that. I buried that baby myself, that night, all open and aboveboard—and any of the crew can tell you so.”

“Probably you did—but it was a foggy night.”

“What’s that got to do with it? I had the watch piped, all regular—read the service, and dropped her overside. Of course, I could have buried her next day, afore the whole company—but I was afraid of cholera spreading, if it was cholera.”

“Why didn’t you let the carpenter sew up the body?”

“Why,” said Randall, “it’s like I told you when I came in. I didn’t want to expose any more than had to be to that cholera.”

“Bah!” my father snorted. “You didn’t want any one to see the fingerprints on that poor baby’s throat.”

“That’s a lie!” Randall cried.

My father could restrain himself no longer. He leaped at Randall like a tiger; struck him a fearful blow on the jaw; picked him up and smashed his fist into the man’s ribs; and then, with a mighty heave, he tossed the man aloft, and brought him down with a crash on the floor. There he lay quiet, a broken and bloody lump of motionless flesh.

“Oh!” I gasped, fearfully. “You’ve killed him!”

“No such luck, sonny!” my father cried—and he tossed the inert body into a corner. Then he threw wide the door, and called Gentry in.

The big mate was quite collected, though his face was grave. He started a little when he noted me; took in the captain with a glance; then faced my father squarely.

“Well, sir?” he said, quietly.

“What did you do with Mrs. Gould’s will and packet?” my father demanded bluntly.

“It was stolen off me!” replied Gentry, as quick as winking.

“Ah! Then you won’t deny having received it?”

“Why should I? Worse luck for me, it was given to me—and I never had intention of denying it.”

“Then,” said my father, “why didn’t you tell me about it when the Mary Louise put in here after coming up from Charleston?”

“Plenty of reason, sir,” Gentry replied. “Them papers weren’t your business, sir—all due respect to you. They was for Mrs. Gould’s sister.”

“So? Well, you don’t mean to say you couldn’t trust me with the knowledge that you had it?”

“It wasn’t that at all, sir,” Gentry declared. “Didn’t I have reason to believe the fewer knew about them papers the better? But way down below that there was another reason. It—”

“Wait a minute,” my father cut in. “You say you lost the will. When?”

“Before we got to Boston.”

“Well, did you report the loss to Mrs. Gould’s sister?”

“Report it?” Gentry snorted indignantly. “Well, I guess not.”

“And why not, pray?”

“Why? I’ll tell you why, by the Flying Dutchman!” And Gentry’s face was growing red. “Because I’m no fool—that’s why! I had the same reason I was going to tell you about—same reason I didn’t tell you. There was Davy gone, Norton gone, baby gone. Soon as I missed those papers, I says to myself: ‘I’m lucky my throat wasn’t cut in my sleep, or that I ain’t been knocked on the head and thrown out the stern port.’ And why should I have yipped to you? I never thought you’d know about it, for one thing. What’s more, where would I have been if I had told you? I hadn’t no proof, had I? No, by thunder! I hadn’t. And that ain’t all.”

“Well?”

“Why, what would you have thought, if I had told you? Look at my position. Wasn’t it quite the reasonable thing for any one to believe that I might have knocked them two—Davy and Norton—overboard? I stood a show to profit by it, didn’t I? Well, that’s what you would have thought—and if I’d told you I lost them papers—had ’em stolen off me—you’d’ve thought just what you’re likely thinkin’ now. You’d’ve thought I sold that will to Gould, and was only trying to cover up, like, in case something leaked out some day.”

And Gentry placed his head to one side, and nodded slowly at my father, watching him through narrowed eyes. “That’s what you would have thought, by the Flying Dutchman!” he resumed. “So I didn’t tell you—no, nor Mrs. Gould’s sister, either. Why should I report such a loss to her, especially when I thought she’d never know it? It’d only be a good way to get my head bashed in some foggy night! Mum was my cue—and mum I keeps. I’m only a mate as yet, and I has a job to keep.”

My father eyed the man a full half minute before speaking again. “Well,” he said then, “I’ll grant there’s something in what you’ve said—if it’s true. But, by God! I think you’re lying.”

Gentry’s neck swelled, and his face reddened.

“Maybe you think because you’re ship’s owner I have to swallow that!” he roared. “By the Flying Dutchman! But I don’t, though. I—”

“You’re guilty as hell, that’s my belief!” my father roared, in equal anger. “You either sold that will, or have it still.” And he aimed a tremendous blow at Gentry’s chin.

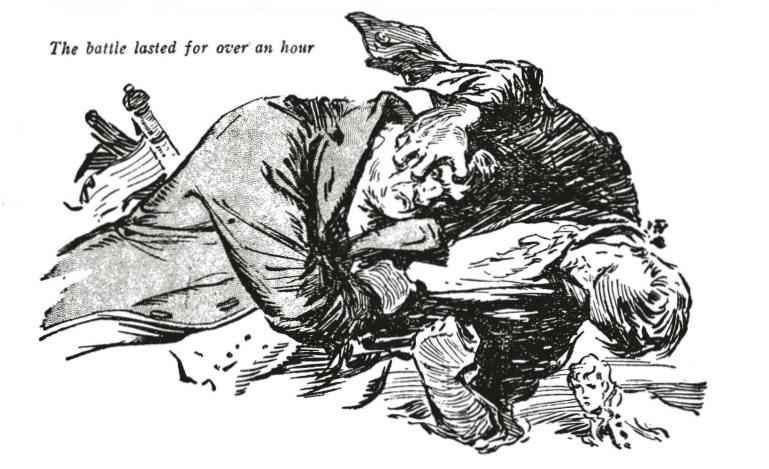

The big mate promptly sidestepped, and countered; and the ensuing battle lasted for over an hour, wrecking the office, and ending in the street, with a howling mob about.

It ended only after the battered and ghastly combatants were forced to stop by sheer weakness. Father had to be taken home in a carriage, and he breathed with difficulty for a month. His face was battered out of all recognizance. But Gentry fared little better. For once he had met his match.

As for Captain Randall, that worthy spent over a month in the hospital before emerging.

Meanwhile the mystery remained unsolved; although Gentry and Randall left Boston, and were eventually listed as shipowners on their own account, the circumstance left the legal aspect unchanged. The assumption that they received the money from Gould to invest in ships could not be regarded as proof. So there the matter seemed to rest for a long period of years.

CHAPTER V. A SALEM INN.

Though both Gentry and Randall selected Salem as a home port after the revolution had ended successfully, I did not come into direct contact with them again until I had passed my thirtieth birthday. Then my father extended his holdings by the purchase of Warren McClung’s shipyard in Salem, and I went there to take over its management. This not only placed me in touch once more with Randall, but gave me news of Gentry’s passing.

“The old Cormoran was put in here for reconditioning by Randall,” said Mr. McClung. “Yes, she’s Gentry’s old ship, but he went ashore with his mate, Blackburn, in Havana last trip, I understand, and never came back. Neither did the mate. Food for fishes, I suppose, after a brawl in some waterfront dive. Well, his boson—named Bagby—brought her back and Randall put in a claim for her. Gentry had no wife and no relatives, ’cept an aunt in Boston, they say; anyway, Randall made his claim good and he’s got her.”

Being still a bachelor, I took up my quarters in the Sign of the Anchor, where Mrs. Webb, the landlady, assigned me to a comfortable suite of two rooms, located on the second floor, and this placed me in daily contact with old Randall himself, for he was living in quarters just below me, on the ground floor.

He was then past sixty years of age and stooped and withered. He no longer sailed the seas, but sent others instead, inasmuch as he now owned three schooners, in addition to the Cormoran. Yet in spite of his worldly success his eye was more furtive than ever, while his gaunt features, pallid now and deeply lined, were those of a man who would be better off without a memory.

And I noted an odd point or two about him. Where he had been aloof and taciturn, he now seemed to seek company eagerly. The long, low taproom, with its beamed ceiling, its latticed windows, and its clean, sanded floors, took up the whole front of the house, and he spent more time here than he did in his own quarters.

All evening he would sit there drinking, ever quick to speak up with a leading question or purchase another round for his seafaring cronies whenever the conversation lagged. I put it down to a pathetic eagerness to drown memory in rum and camaraderie.

Another point I noted had to do with the seaman Bagby, who was known as “the boson,” just as though no other man of that rank had ever put to sea. He was a huge, hulking, sullen man, with a bullet head and piggish eyes; and his square, smooth-shaved face had been turned blue from an excess of rum.

All day—so my garrulous landlady told me—the boson prowled about the beach or went afishing, with no attempt to get another berth at sea; nor had he performed any other work since his return to Salem with the Cormoran. Yet, she informed me, he occupied a good room at the front of the house, on my floor, and for the past six months had paid his bills regularly. Usually he would not answer when addressed; only look up with a flame in his small eyes and growl, and few seemed to care for his company.

Though he and Randall met frequently, they exchanged mere grunts, or spoke not at all; but on two different occasions, when the big boson was drunk on rum, I saw him summon Randall curtly with a jerk of his bullet head. Nor did the old shipowner linger long in stays. Both times he arose—albeit with a frowning face—and accompanied the boson to his quarters.

What this portended I did not at first surmise; but Mrs. Webb came into my sitting room one evening at the end of my first week and stirred up the old fire anew.

“It ain’t that I should be talkin’ about a payin’ guest, I suppose,” the little woman began, apologetically. “Cap’n Randall, I mean. But just the same—and I’m not asking just out of curiosity, Mr. Waltham—I wonder if you’d give me the straight of that mix-up on the Mary Louise, years ago.”

As I hesitated her little black eyes snapped with ready comprehension, and she hastened to explain.

“I’m asking,” she declared, “because I think the old devil had some’at to do with Cap’n Gentry’s taking off—so there! I’m a friend of old Mrs. Peabody, Gentry’s aunt, who might’ve claimed the Cormoran and had enough to last her the rest of her days, poor old thing, only Cap’n Randall produced a note from Gentry and took the ship over.

“Now I don’t think Bill Gentry ever signed any such note; no, nor I don’t think as he ever would have borrowed a shilling from Cap’n Randall under any circumstances. He used to stop here when he was in port, and I know he had no use for Cap’n Randall.

“But all that aside—there’s something else I’ll tell you if you’ll help me get the straight of the Mary Louise business.”

With my curiosity aroused, I complied with her request. Her eyes, which reminded me of little black buttons, never left my face during the recital.

“There!” she exclaimed when I had finished. She leaned closer to me, then, and declared: “I don’t think that will ever left Gentry’s hands while he was alive!”

I straightened, eagerly. “Why?” I cried.

“He had a little strong box, all polished, with brass bound corners and an inlaid top. He never left it aboard his ship when he came here. Well, sir, that box wasn’t on the Cormoran when she was brought back. I had told Mrs. Peabody about it, you may be sure. But when she asked about it, why, this boson, he ups as bold as brass and says: ‘Sure! Cap’n Gentry never left that box aboard ship no place he anchored. He took it ashore with him there in Havana—and that was the last I see of him.’ ”

“Then what is your theory?” I asked.

“I think Cap’n Randall got the contents of that box,” she declared. “What’s more, I think the will was in it. If not, why would a man named John Gould be coming here from England?” And she leaned back triumphantly.

“How do you know that?” I cried.

She eyed me shrewdly, then tossed her head a bit defiantly. “Oh, I’ve been looking around. Found his letter, among other things—his letter to Cap’n Randall. It was just a short letter, saying he would sail from Bristol on the Atlanta her next trip. She’s due in Boston some time this month. Anyway, I think Randall has that will, and now he’s going to sell it to this Gould.”

CHAPTER VI. A PLEA FOR HELP.

I digested her words for a moment in silence.

“I’ll grant it is not at all unlikely,” I said at last. “Still, it’s only a guess.”

“But you’d be willing to help, wouldn’t you, if there was a chance to prove it?” she cried eagerly.

“Most assuredly.”

“Well, then, I’ll tell you this: it isn’t all supposition on my part. You see that chimney there?”

I glanced at the chimney in the east wall. It was now the middle of July, and the stove had been removed from the room, but the chimney contained an aperture for a stovepipe, now closed by a plate.

“That chimney,” she said, “runs down to the grate in Cap’n Randall’s sitting room. Pull out that plate, and you can hear what is said in that room fairly plain. Well, I wasn’t above trying to catch something that way, a time or two when the boson and Cap’n Randall was down there. And I did catch something. I know he—Cap’n Randall—did get Gentry’s papers out of that box.”

“Ha!” I cried. “That’s more definite.”

“Yes,” she said. “But I couldn’t find them. Oh, I searched, all right, times when he was out—but his chests are under heavy locks, and ’twasn’t much use. But here—I’ve thought it over, and I’ve wondered if you’d think it advisable to swoop down on him with a search warrant from Magistrate McCullom.”

“But you can’t swear Randall actually has the will, can you?”

“No,” she replied, “I can’t. All I heard was something about ‘them papers.’ ”

It was necessary, I judged, to have definite knowledge of the document’s existence and location, before trying anything drastic; and, after some further discussion, Mrs. Webb agreed with me. We decided to wait for John Gould’s arrival, with the intention of trying to overhear something more definite at that time; for, even though we were correct in assuming that Randall had the will, a bailiff’s search might not only fail to disclose its whereabouts, but would cause the frightened conspirator to destroy it at his first opportunity. And so matters were standing when, three days later, a young woman was ushered into my private office at the shipyards.

She came toward me with a quick, springy step and her keen eyes full on mine.

She was about twenty years of age, with an exquisitely tinted countenance, eloquent of intelligence and fire; a woman who gave the impression of tallness, though I topped her by half a head; a woman with a strong figure, molded in long, lissom curves.

Her clothing was of inexpensive material, such as might have been worn by a maid or governess, and she wore a high-crowned, beribboned bonnet which came down to the tips of her ears and which covered her temples and shadowed her features. Those strands of hair visible to me were shot with the rich reds and browns one sees in the sheen of a turkey’s wing; but her eyebrows were very black, with a habit, as I was soon to discover, of twitching humorously.

Just then, however, there was nothing humorous in her aspect. She had the chin of one who would dare say anything, and a wide but firm mouth; and she had an air of sophistication, though there was nothing suggestive of impropriety about her. Yet she was not quite assured as she faced me. Instead, she seemed a bit nervous; her color was quite high, and her eyes could not wholly hide the fact that she was laboring under excitement.

“Mr. David Waltham?” she said—a bit hurriedly and even somewhat tremulously. “My name is Mary Channing.”

I bowed and placed a chair for her. Her voice was very pleasing in tone.

“I know you’ll think this most unusual,” she went on quickly. “But doesn’t the name recall anything to you? And—do I look like any one you have ever seen?”

“No,” I said slowly, studying her closely. “I can’t say—”

A shadow of disappointment fell over her face.

“Well,” she said, “I was in hopes you might see some resemblance to the woman who died on your father’s schooner—or so I’ve been told—many years ago. You see, I’m a niece of Miss Gertrude Channing.”

I sat up then, abruptly. “A niece of Mrs. Gould’s sister?” I cried.

“Yes!” she declared excitedly. “And oh, Mr. Waltham, I’ve come to ask you about the happenings on board that schooner.”

“I wasn’t aware that Miss Channing had any relatives on this side of the water,” were my first words.

“You know her, then?” she asked, quickly.

“No,” I replied. “My father had some letters from her, years ago, but I never met her.”

“Neither have I,” she said. And when I eyed her curiously at this statement, she blushed deeply and hurried on:

“But let me explain. I was born on this side of the water, and my parents died when I was young. Then—comparatively recently, I heard the Mary Louise story, through the woman who raised me. And she had heard it through a sea captain who was discussing Captain Gentry’s death in Havana.

“I’ve come here from New York just on the strength of what I’ve heard—but it may be that I’ve come on a wild goose chase. I can tell, though, if you’ll answer my questions.”

“Why, I’ll be glad to tell you what I know,” I said. “But don’t you think you might be a bit more explicit? Why do you want to know the exact facts?”

She dropped her eyes, and flushed anew. But in the next breath she raised her head, and eyed me with a faint trace of shame, and some defiance. “Suppose you were a girl, Mr. Waltham, and circumstances had made you a barmaid—”

“Not a barmaid?” I cried. “You don’t look—”

“Thank you, Mr. Waltham!” she said, rather dryly. But she went on, almost at once, “I didn’t want to tell you of that. But suppose you were a barmaid—or had been a barmaid—and you heard there was a will which might change your whole life, and you had been raised by a woman who ran a grog shop, who thought the life of a barmaid was quite good enough for you—well?”

“Why, I’ll gladly tell you anything I know,” I said.

“Oh, thank you!” she cried, smiling radiantly. “Then there was a will?”

At once I plunged into the Mary Louise story.

She quickly became serious again, and through it all she sat forward on the edge of her chair, with her eyes snapping, her hands clasping and unclasping, and her color ebbing and mounting. Now her eyes filmed with tears; now her lips closed grimly. But when I came to the latest developments her excitement increased, and her eyes shone like stars.

“That does put a new light on the matter!” she cried, when I had finished. “Why, I came here only expecting—” But here she broke off, abruptly, and stared out of the window, with her hands clenched. Suddenly she wheeled on me. “I feel sure that the will must still exist, and if I can I’m going to stay here and at least try to get it!” she declared.

“It’s only a supposition, you must remember,” I pointed out. “The baby is dead. Mrs. Gould’s sister, your aunt, may be dead also. There’ll be litigation and delay, even if you should get this will. You’d have a long, laborious process, too, in proving your identity—”

“I can prove that when the time comes!” she cut in. “And I’ll take all the other risks. I realize it’s a long chance, but who ever won anything in this life without trying? I—I’m wondering if you’ll help me?”

“I will do anything I can, Miss Channing.”

She thought a moment. “You’ve said Mrs. Webb appears sincere in her desire to help Gentry’s aunt regain her rights. You are sure of this?”

I nodded.

“Then will you give me a note to her—just a little introductory note, saying that I’m interested in the Mary Louise story, too?”

With this request I complied readily enough. I would have detained her for some explanation of what she had in mind; but here she begged my temporary indulgence, saying that she intended to ask Mrs. Webb for a place at the inn, and would gladly take anything that offered, even though she had to work as a scullery maid. “Further plans will depend on Mrs. Webb’s attitude.”

That noon, when I entered the inn, Mrs. Webb followed me to my sitting room.

She always wore a shell-back comb at the back of her shapely head, with a little lace cap atop her coil of gray hair; and this was now somewhat disarrayed, while the stiff little curls beside her ears fairly shook in her excitement.

“Mr. Waltham,” she cried, “you sent that girl to me this morning. Do you know anything about her, ’cept what she told you?”

“Not a thing,” I said—and I briefly outlined our conversation. As I talked, pink spots glowed in Mrs. Webb’s stiff, parchmentlike cheeks, and her little piercing black eyes watched me closely. In their depths was a twinkle which I could not quite understand.

“Well, sir,” she declared, “you get hard as nails running an inn, and don’t trust much—but I’m taking her in on her say-so. You wait till you come home to-night, and you’re apt to get a surprise.” With which enigmatical statement she whisked away.

CHAPTER VII. THE MASKED BARMAID.

The surprise was waiting for me when I returned that evening, for I found Mary Channing behind the little semicircular bar—wearing a narrow black mask.

Her merry gray eyes, with flashes of green in their depths, twinkled at me through the slits; but when I seized the first opportunity for a word alone with her, and asked the reason for the mask, she said, demurely, “It’s Mrs. Webb’s idea. Ask her.” Nor was Mrs. Webb very explicit. For when I asked her, she smiled at me, roguishly, and cried:

“Why, it’s killing two birds with one stone. Causing a lot of talk, isn’t it? And that makes trade.”

“Are you two planning to rifle Captain Randall’s quarters?” I asked.

“Why—I’ve already tried that. No use. But I’m going to do whatever I can to help her get that will, if it still exists.”

It piqued me to sense that they were not taking me wholly into their confidence: and I found myself growing more and more curious about this masked barmaid. She had manifested an abhorrence for the calling—if it may be termed such—when she first talked to me; yet now I found her apparently enjoying it.

Of course I realized that she had a motive; but it irritated me strangely to see her serving other men with drinks. On the other hand, it pleased me when she came to serve me, and irritated me anew at the very fact that I had allowed myself to be pleased! For, after all, whether she was related to Miss Channing or not, the fact remained that she had been a barmaid, and was a barmaid still.

I determined to be no more than ordinarily courteous when she came to serve me. But events so shaped themselves that my name was linked with hers before the second night had passed.

Her advent had caused a deal of talk. Questions about her and the mask flew quickly from tongue to tongue on the first night. And even the boson came out of his sulks, revealing his yellow, broken teeth in a grin.

“What mought I call ye?” he asked her.

“Why,” she replied, laughing pleasantly, “you might call me Miss Tee-rious.”

He slapped the table at this, and his grin widened. “And when mought I call on ye?” he cried.

“When you want a drink, and have money to pay for it!” she retorted instantly.

This was greeted with a guffaw from the onlookers; all the others took her chaffing in the best of good nature, but the boson sulked under his rebuke. So, on the next night, when he grew more than ordinarily drunk, he lurched up and attempted to snatch off her mask.

Turning so quickly that I could hardly follow her movements, she tripped the man, and sent him sprawling, full length on the floor. He came up again immediately, and I thought he was about to strike her; but by this time I had started toward him, and, coming at him side-on, I caught the tipsy brute with a shove that knocked him over.

He started up again, and whipped out his dirk; but I kicked this weapon from his hand, and knocked him unconscious with a blow to the chin.

In the hubbub that followed this, Mary spoke quickly into my ear.

“Thank you, Mr. Waltham,” she said. “I’m sorry, though, you had to be dragged into a brawl over a barmaid.”

Cold perspiration broke out all over me. Knocking down a bully in a woman’s defense is one thing; engaging in a public brawl over a barmaid was quite another thing. I made some inarticulate rejoinder and hurried into the outer darkness.

The boson apparently had no desire to seek open revenge, though he glowered whenever I came near him thereafter; but the brief affair caused a deal of talk, nevertheless, and I found myself the target for a deal of good-natured chaffing, particularly from Mrs. Webb.

My cheeks flush easily, and she seemed to find amusement in twitting me about the affair; nor did she seem to be impressed when I told her, rather heatedly, that I would have done as much for any woman.

And well she may have smiled! Before another week had gone by, the expected arrival of John Gould, and the Mary Louise mystery were secondary considerations with me. Mary assuredly made no attempt to thrust herself upon me; but there was that in her smile, or the demure flash of her eye, or her chuckling, infectious laugh which haunted me.

So matters were standing at the end of the week when, as I was sitting late one night in talk with a skipper, I noted Captain Randall being helped off to bed by two of his cronies. It was an unusual circumstance, since the old rascal seemed able, as a rule, to down great quantities of rum without showing the effects.

Mary had left the room, and Mrs. Webb had been serving Randall’s table; but at the time I gave this little thought, and, shortly afterward, took leave of my friend, and went upstairs. There, as I turned into the dark hall which ran from north to south past my room, I bumped full into the masked barmaid.

“Heavens!” said she.

“Hell!” said I—though I had intended to say nothing of the sort.

She laughed low. “Well, Mr. Waltham,” she said, “that is where all Barmaids are headed for.”

My hands had leaped up, at the moment of contact, so that I had caught her arms. Her tresses had fallen, in a thick cloud, down across her shoulders and breast, and I winced inwardly at the thrill their touch gave me.

“You seem to find me a source of amusement!” I said, with some heat. “That would be excusable, perhaps, if I had ever made any silly advances—”

“Silly, sir?” I felt her shoulders stiffen a bit. “You mean it would be silly of me to think you would ever make advances to me—a barmaid—don’t you, Mr. Waltham?”

“I didn’t mean anything of the sort!” I declared, heatedly. “I simply meant I haven’t made any advances—”

“Then,” she cut in, “perhaps we are to waltz?”

I lowered my hands instantly—and I wonder my ordinarily dark features did not illumine the hallway.

“That,” I stammered, “was involuntary!”

“I understand,” she said, quite primly. She started to move—and then stopped, with a little gasp. “I believe,” she whispered then, “that my hair is caught on your coat button, sir.”

In confusion my hands came up, and so encountered hers, groping for the button. My head whirled, and I seized her fingers, pressing them against my breast.

“Those involuntary hands!” she murmured.

“See here,” I cried, “do you think you have treated me fairly?”

“A barmaid—treating Mr. Waltham fairly?” she whispered with a chuckle.

Knowing full well that she had read me as easily as a sailor judges the weather, I nevertheless hated to admit that the difference in our positions had been the cause of my resentment after that brawl. So I hastened on:

“I mean in the matter of the Mary Louise mystery. I know you two women are scheming. Won’t you tell me what you have in mind?”

“Oh!” she whispered, quietly disengaging herself. She listened for a moment. “We have something in mind,” she admitted. ‘“But we weren’t sure you would approve of it.”

“But I want to help all I can.”

“Well,” she whispered, “had Captain Randall gone to bed when you came up?”

“Yes,” I said. “He was very drunk.”

She drew a sharp breath. “Mrs. Webb said she intended to put a drop in his grog,” she whispered, excitedly. “And when he’s fast asleep we’re going to open the big chest in his quarters. We’ve found out that he keeps the key hanging from his neck. Now, sir, do you want to help in that?”

“I do,” I said instantly. “I think it’s justifiable in this case.”

“Then come with me,” she said, “to Mrs. Webb’s rooms.”

CHAPTER VIII. BURGLARY.

Gaining admittance into the captain’s quarters did not prove very difficult. After waiting until we were certain all the guests were in their rooms, and I had secured my derringer, we went down the back stairway and into a hallway which lay between the dining room and the quarters on the east side of the house.

Mrs. Webb produced a passkey, and we entered an empty room adjoining the captain’s bedchamber. Here we paused and listened for the man’s snores; and, assured that he was sound asleep, Mrs. Webb unlocked the intervening door, and we entered the bedroom.

“That drug’ll hold him for some few hours,” said Mrs. Webb, in low tones. “So we ain’t got to worry none about him. But we’ve just got to have a light.”

Forthwith she made haste to lower the windows, and draw the curtains; whereupon I busied myself with flint and tinder, and lit a candle.

Captain Randall lay on his bed, breathing stertorously. His friends had not troubled to undress him, having merely removed his shoes and his coat. So he lay flat on his back, with his arms outflung, and one leg dangling over the edge of the bed, pallid, unwholesome, disgusting.

It was the work of but an instant to open his shirt and disclose the string around his neck. Two keys—one small, and one large—were attached to it. He merely groaned a little when I lifted his head and slipped the string over it.

The captain’s big locker was under his bed. It was a heavy box, painted blue, with a brass name-plate screwed into the top, and the corners were also bound with brass. With some difficulty I pulled it out beside the bed, and unlocked it.

“We must be careful now,” Mrs. Webb warned, as I threw back the lid. “We’ve got to replace every article just so—’specially if we don’t find that document.”

“Ah, but it must be here!” Mary whispered. Her breathing was very rapid now, and her eyes shone feverishly.

“Well, we’ll see, deary,” Mrs. Webb rejoined, pressing the girl’s hand.

Not much of interest to us was disclosed in the top tray: three account books in one compartment, and in the others some twists of tobacco, a brass telescope, an image of Buddha, several small, highly polished seashells, a Chinese fan, a silver-mounted pistol, a sailor’s sewing kit, a bundle of charts, and some works on navigation.

Nor did we find any papers in the next tray, where the captain had spread a blue coat, almost new, decorated with brass buttons. But in the bottom of the locker, under an old waterproof coat, we found a small strong box.

“That small key!” Mrs. Webb whispered excitedly.

My fingers shook as I unlocked this box, for my hopes had been mounting with each passing second; and I scanned the contents eagerly. There were several letters, one bundle being tied with ribbon—a strange thing to find in this man’s possession!—and a canvas sack filled with coins. There were also several folded papers. One of these proved to be a note from William Gentry to Andrew Randall for the sum of ten thousand pounds. But the packet we were seeking was not there!

“It just must be here somewhere!” Mary whispered, with a little catch in her voice.

“I’m not beaten yet!” Mrs. Webb declared grimly. “The old curmudgeon! What would he be wanting to see that Gould for, I’d like to know?” Whereupon she began a search of the bureaus and a closet in the captain’s sitting room.

“More’n once he’s shut hisself up here for a day at a time,” she said vindictively. “That old fox! I think he’s got another hiding place here somewhere.”

We searched for a half hour or more, even trying the fireplace for loose bricks; but at last we were forced to acknowledge ourselves beaten, and I reluctantly replaced the contents of the locker, shoved it under the bed once more, and slipped the string over the captain’s head.

“You see that?” Mrs. Webb whispered, pointing at a loaded pistol under the man’s pillow. “He’s never at ease, that man. Alius has that around. But there, deary, don’t you give up.”

She took Mary by the shoulders. “That will was still around a year ago and Gentry had it.”

“What?” we cried in unison.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Webb. “It was in that box of Gentry’s I told you about,” and she tossed her head with some little defiance. “I ain’t a braggin’ of it, but I had my reasons for doing the same with Gentry as we have with this man to-night. That’s how I saw that will. The whole packet you told me about, too.

“I didn’t know just what it all meant. ’Twas only afterwards, when I got the Mary Louise story straightened out, that it all got clear to me. But I didn’t say anything—just put it back and said nothing. I’d rather have crossed a typhoon than that Bill Gentry, anyway—and I’ve learned to think a deal before I put an oar in. But there you have it. It stands to reason that thing’s here somewhere, doesn’t it?”

“It certainly does!” Mary exclaimed, with manifest delight. “But where, where?”

“Looks like we’ll have to wait until that young Gould gets here,” said Mrs. Webb. “So let’s to sleep.”

This time, after listening carefully for signs of movement, we emerged into the lower hallway with the candle still lighted. And, when Mrs. Webb had preceded us, and Mary and I were standing on the second floor landing, near the stairs which led up to the servants’ quarters on the third floor, I detained her a moment.

“Please take off that mask a minute before you go up,” I pleaded. “I haven’t seen you without it save once, and then you had that bonnet on that shaded your face.”

“S-hhh!” she whispered, finger on lips, and quickly blew out the candle. Some one had started up the front stairway.

Whoever it was went directly to one of the rooms at the front of the house, but my chance was lost.

“Damnation!” I muttered.

She laughed low in her throat and I caught her by the shoulders.

“If I made you believe I didn’t want to make advances, it was a lie,” I whispered. “I’ll not let you go until you promise to meet me somewhere.”

“Why, you see me every day, sir.”

“But, if you could slip out to the beach—”

“Where we can’t be seen by others?”

“Why,” I said, “isn’t it the custom, when a man would talk to a maid, to seek seclusion?”

“And a mossy dell, I believe.”

“Or a stile, perhaps,” I rejoined, trying to meet her on her own ground.

“No!” she declared. “I tried that once, and, climbing over, I caught a splinter in my stocking.”

“So!” I gripped her very fiercely. “You have had affairs!”

“Also pangs, Mr. Waltham. Those stockings cost me a crown.”

“Please be serious!” I cried.

She laughed. “Well,” she conceded, “if you’ll escort me from here, I’ll go with you to-morrow night, after I come off duty. That will be at ten, tomorrow night.”

I groaned inwardly. Walking away with the barmaid from this inn! Unthinkable! And then, because the aroma from her hair was too alluring and too maddening for me, I buried my face in it and cried, “Kiss me!”

“Ah!” she whispered. “But osculation with barmaids is dangerous, Mr. Waltham.”

I choked.

“But you may,” she went on, “kiss my hand if you wish.”

Her hand! A barmaid’s hand! Shades of Caesar! But I, David Waltham, kissed that hand, and counted it a privilege.

CHAPTER IX. BILL GENTRY RETURNS.

Next morning, at the breakfast table, a serving maid told me that Mrs. Webb had been summoned during the night to go to Boston, where her son was very ill, but this news was quickly driven from my mind. For, when I stepped into the taproom on my way out to my office, there stood Roaring Bill Gentry, leaning on a pair of crutches!

He was now fifty and a bit gray, but there were the same tremendous shoulders, the identical beak of a nose, and the same keen, twinkling, crafty eyes, with the long eyebrows twisted upward, like a devil’s horns.

He was wearing a smooth broadcloth blue coat, with shining brass buttons, and a fine cocked hat was tipped back on his great head; and though the leathery folds on his cheeks showed more cross-webbed lines, the years had made but little change in his bronzed, craggy features.

Sight of him brought me to a full stop, whereupon he spoke up.

“You seem to know me,” he boomed out in his deep, melodious voice. “But I can’t quite place you, somehow.”

“It’s been many years since you saw me,” I said, rather curtly. And I told him my name.

“Not Davy!” he cried, with a start. An odd flicker of light appeared for a second in his shrewd, half-closed eyes. But in the same instant he had recovered himself and was smiling. “Well, by the Flying Dutchman, if it ain’t, may I be scuttled! Tall as me and nigh as heavy, I should say, too.”

And he chuckled. “Why, I’d ought to have known you—though it’s a long time. Same long, dark face; same black eyes; same stubborn chin. But here, this ain’t shipshape, this ain’t! Let’s have a wring of your flapper, Davy—unless you still feels like the old man did?”

“A handshake between us would be an idle pretense,” I told him, thrusting my hands into my pockets.

He looked hurt and eyed me reproachfully.

“Does you and your dad still think I knocked you overboard?” he said.

“It looks very much that way,” I said bluntly. “Appearances are certainly against you. The man who threw me over didn’t have to hunt very far for me—though I admit I yelled and gave my position away. It might have been Captain Randall, of course; but with all that aside, how do you explain your ownership of the Cormoran?”

“Explain it?” he cried testily. “You, a builder and shipper, ask me that? With conditions the way they’ve been at sea the past twenty years or so? Why, by the Flying Dutchman! thousands of ships have changed hands at sea—and you know it.”

“You got her before the war,” I pointed out. “If you mean to infer that you captured her, I know better. The record of sale shows you bought her.”

“Never denied that, did I?” he retorted. “But you see here: they called it privateerin’ during the war, but I never saw much difference in privateerin’ than flying the Jolly Roger out and out, by thunder!

“Well, now, I ain’t denyin’ I made a haul afore the war, when I got funds to buy that Cormoran—and I knows, too, I didn’t have no piece of paper with me from the Continental Congress when I did it, ’cause there weren’t no Continental Congress. Maybe”—and he became sarcastic—“I shouldn’t have grabbed a chance to feather my own nest. King’s ships was grabbin’ cargoes right and left on the pretext of punishin’ smugglers o’ contraband; but maybe I should have overlooked them things, and let old King George grab it all. And when it comes to the pot callin’ the kettle black, Davy, you and your father had several privateers out during the war, didn’t you?”

“Exactly,” I replied. “And accounted for every capture, as well as the losses.”

“Well,” he shrugged, “that’s neither here nor there. Point is: here we are bow on. Now you look old Bill straight in the eye. Do I look like one who would bring a slip on your cable?”

“No,” I admitted, “you don’t. But I’m older now, Bill Gentry, and looks don’t mean as much to me as they did. But see here: there’s your old Cormoran, riding out there beside the Elsie, taking on salt fish and some lumber for the sugar islands. We finished reconditioning the Cormoran this week. Have you heard about that yet?”

“Yes,” he said with an oath. “My old aunt told me. I’ll have her back afore sundown, and you can lay to it.”

“Why,” said I, “they told me Randall had your note.”

“I never signed no note!” Gentry declared.

“Then,” said I, looking at his crutches curiously, “it would appear that some one tried to have you put away, there in Havana.”

“Maybe they did,” he said shortly. “Knife stab in the back hurt the spine, and now I can’t rightly use this right pin yet. But I’m making no charges, you understand—I’ll deal with him first.”

Just then the little hallway leading into Captain Randall’s quarters opened, and he came out. Sighting Gentry, he stopped. All color fled from his face, and his jaw sagged, while his eyes were black and staring, for all the world like some guilty soul who has been brought, quite suddenly, face to face with the devil.